Lexi Wei

27 Oct 2025

YK Pao School

Abstract

Drawing on psychological research conducted during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, this essay aims to explore the pandemic’s impact on the long-term psychological development of children. In specific this paper will focus on how stressful situations created by the pandemic can be translated into developmental challenges for children through the mediation of their parents, as well as social isolation due to lockdowns and their resultant obstruction proper social skill development. Stressful situations experienced by parents (e.g. change in parents’ working conditions, loss of a loved one, diagnosis within the family, change in child’s routine and school) can translate into compromised parenting practices and ultimately disrupt children’s development of emotional regulation skills and healthy attachment patterns. Additionally, prolonged periods of social isolation from school lockdowns have limited children’s exposure to interactions with their peers and teachers, depriving many of the necessary conditions for healthy socioemotional development. Through the examination of these factors, this essay will prove the left long-lasting developmental imprints the COVID-19 pandemic has left on the psychological growth of an entire generation.

Introduction

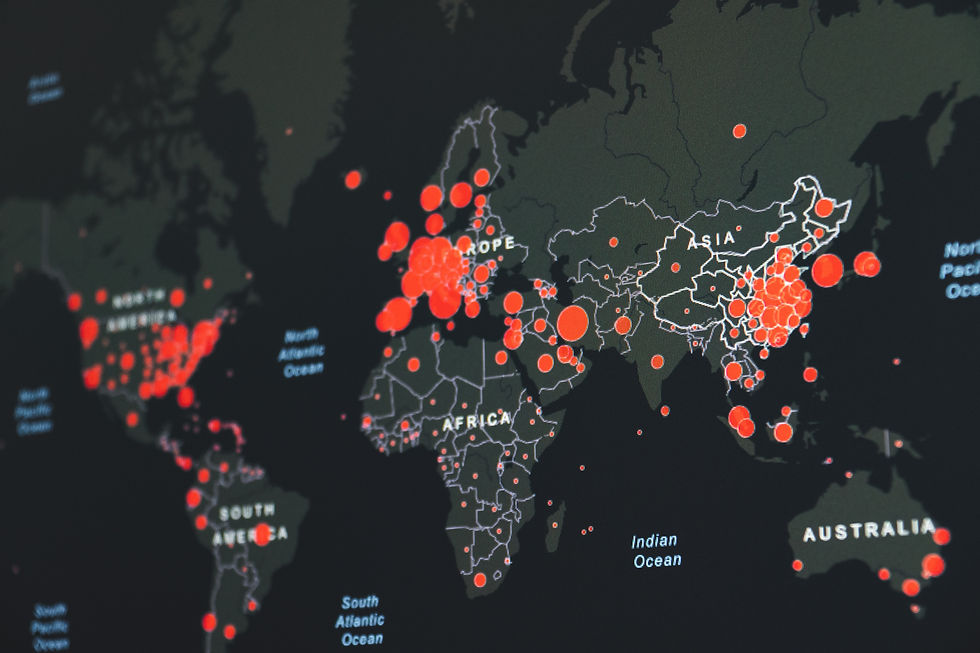

Imagine this: a fifth grader in Poland staring at a Zoom screen for the sixth hour of that day, wondering why she couldn’t go out and play. Two years later, she’s at home in Shanghai, again staring at her computer watching news about the newly initiated lockdown rules. Unfortunately, this child is not alone, nor one only of our imaginations. Since its outbreak in 2019, COVID-19 had not just posed a direct threat to our physical health, with economies obstructed, cities locked down, and people’s routines disrupted; it has also drastically changed how we interact with the environment and the people around us. COVID-19 has-been exceedingly impactful especially on the younger generations because of its profound influences on their long-term psychological development, which can extend far beyond the duration of the pandemic itself. In this article, I’d like to explore the psychological impact of COVID-19 on children and their long-term development through two key contexts: parental stress and social isolation.

Stressed Parents: The “Cascade Effect”

It would be amiss to look at COVID-19’s psychological impact on children without considering the family as a system. In one study focusing on US families with children aged between 6 and 12, the relationships between parent emotional health, child emotional and behavioral health, quality of parent-child relationship, and the amount of stressful situations the parent might experience due to the pandemic (e.g. change in parents’ working conditions, loss of a loved one, diagnosis within the family, change in child’s routine and school) was studied (Bate et al., 2021). Interestingly, results showed that COVID-19’s stressful impact was positively associated with parents’ emotional health issues, but not children’s emotional and behavioral health. However, there was a positive association between parents’ emotional health and children’s emotional health, which was moderated by the quality of the parent–child relationship (Bate et al., 2021). This suggests that a great deal of the negative psychological impact caused by COVID-19 reached children not as a direct cause, but through the mediation of their parents. This corresponds with previous literature indicating that COVID-19 related stressors impacting one family member may have a cascade effect and ultimately influence the functioning and well-being of other family members (Prime et al., 2020).

The core mechanism that seems to lie behind this are emotional regulation. Defined as “the awareness, understanding, and acceptance of emotions, and the ability to act in desired ways regardless of emotional state” (Gratz & Roemer, 2004), emotional regulation skills have been widely established as crucial in coping with stressful situations. Importantly, parents’ competence in emotional regulation has a huge impact on whether their children can successfully learn emotion regulation skills, as children can learn to regulate their emotions by observing their parents’ emotion regulation strategies and by experiencing a supportive and emotionally regulated family climate during their early development (Rutherford et al., 2015). Research has shown that, during times of high stress, parents themselves might find it difficult to manage their own emotional responses, such as fear and hyperarousal, to the extent that their ability to support their children in learning effective emotional coping skills are compromised (Cohen & Shulman, 2019). Apart from this, parents with higher levels of stress were found to be more likely to employ hostile, disengaged, or punitive parenting styles (Shorer & Leibovich, 2020). This meant that stressed parents were more likely to show aggression when interacting with their children, be less attentive to their needs, or use punishing measures more in parenting. All three of these parenting styles were associated with poor regulation of negative emotions in children (Fabes et al., 2001). All these researches exhibit the complex ways the pandemic could influence a child’s long-term wellbeing, as patterns of emotion regulation are often learned during one’s early years and carried into adulthood.

To further illustrate the developmental impact of COVID-19 on a child’s psychological growth, we can bring up the example of a certain group of children, such as those whose parents were healthcare workers. During the pandemic, long working hours and increased risk of COVID-19 infection became a norm for health workers around the globe, which meant their children often had to endure extended periods of separation from their parents. This could have long-standing effects on small children and infants, as frequent and sustained interactions from caregivers during the first 6 months of life is crucial for developing a healthy internal working model of attachment (Bowlby, 1969; Heinrich, 2014). Formed implicitly through the infant’s experience with the caretaker, the internal working model contains mental representations of the caretaker’s likely behavior patterns (e.g. when attention would be given and under what circumstances), which then contributes to core beliefs about like whether “people can be trusted” and whether “this world in general is a benign place” (Sherman et al., 2015). The internal working model can and is often carried into adulthood, playing a significant role in determining one’s patterns of forming intimate bonds or social relationships in general. This further illustrates how COVID-19 can leave long-lasting developmental marks on children’s abilities to form interpersonal relationships, as an infant with a constantly absent parent could fail to develop a healthy internal working models of attachment and grow to hold implicit, pessimistic beliefs on intimate relationships.

School Lockdowns: Social Isolation and Socioemotional Development

In addition to the role of a children’s micro and macroscopic social constitutions, I believe it is important to also examine the broader social landscape during COVID. By April 2020, about half of the world's population was under some form of lockdown, with more than 3.9 billion people in more than 90 countries or territories having been asked or ordered to stay at home by their governments in social isolation (Sandford, 2020). What was alarming for the children were the negative influences of social isolation that extended beyond the surface-level changes in daily routines. For example, reduced physical activity levels, which ultimately has led to sedentary lifestyles and obesity (Andersen et al., 1980), and prolonged screentime which could lead to poor sleep quality (Haleemunnissa et al., 2021). Social isolation poses serious obstacles for children’s long-term cognitive and socioemotional development that could fundamentally impact the way they perceive and interact with both themselves and the world.

Social interactions are crucial for children because they provide the opportunities to learn cultural values (Brown et al., 2019), develop an understanding of social norms (Staub, 2013), and to help children develop socioemotional skills, which is essential to developing long-lasting and meaningful relationships with their peers and adults (Meins, 2013). An important component of these socioemotional skills is the ability to recognize emotions in others (Dowling, 2014), allowing the child to develop a sense of empath, a skill of utmost necessity when living within a social group (Masterson & Kersey, 2013). This sense of empathy can only be developed from experience, from the accumulation of observations of others’ emotions and reciprocal communications of emotions. As a result, the absence of school, peer exposure, and community activities during quarantine would deprive children of the social exposure necessary for the socioemotional developments. To take Ireland as an example, from March to September 2020, school campuses were closed due to a national lockdown, during which children mainly interacted with parents and siblings, and had limited opportunity for daily social interaction with school peers and teachers (Symonds et al. 2020). A study focusing on primary school students from 9 to 13 years old in Ireland found that after 5.5 months of lockdown, children’s self-reported ability to manage peer relationships had a significant decrease (Hanley et al., 2022), and Hanley et al. attributed this result to past findings that showed an interruption to children’s typical patterns of social interaction could negatively impact their social development (Dyregov et al., 2018). This could have particularly significant developmental consequences viewed under the sociocultural perspective, as middle childhood has been established as a critical sensitive period for the development of children’s higher order thinking processes (Vygotsky & Cole, 1978) such as the metacognition necessary for monitoring and controlling emotions and social interactions. These thinking processes are learned through children’s interaction with others and would become integrated in the mental structure of the individual (Vygotsky & Cole, 1978).

Conclusion

Through the analysis of various studies under a psychological and cognitive development lens, we can clearly see the long-lasting impacts the COVID-19 pandemic has left, especially on the younger generations. At home, children often had to negotiate developmental challenges in particularly demanding conditions such as under unhealthy parenting styles or parental emotional dysregulation caused by COVID-induced stressful situations. Not only did many had to navigate turbulent family dynamics, many experienced long periods of social isolation due to school lockdowns, putting them in a situation which lacked the social exposure necessary for the normal trajectory of socioemotional development.

References

Andersen, K. L., Seliger, V., Rutenfranz, J., & Masironi, R. (1980). Physical performance capacity of children in Norway. European Journal of Applied Physiology and Occupational Physiology, 45(2), 155–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00421323

Bate, J., Pham, P. T., & Borelli, J. L. (2021). Be My Safe Haven: Parent-Child Relationships and Emotional Health During COVID-19. Journal of pediatric psychology, 46(6), 624–634. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsab046.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss, Vol. 1: Attachment. Attachment and Loss. New York: Basic Books.

Brown, J., Smith, L., & Thomas, A. (2019). The role of peer interaction in child development. Journal of Child Psychology, 45(3), 223–240.

Cohen, E., & Shulman, C. (2019). Mothers and toddlers exposed to political violence: Severity of exposure, emotional avail-ability, parenting stress, and toddlers’ behavior problems. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 12(1), 131–140. doi:10.1007/s40653-017-0197-1

Dowling, M. (2014). Young children's personal, social and emotional development. Sage.

Dyregrov, A., Yule, W., & Olff, M. (2018). Children and natural disasters. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(sup2), 1500823. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2018.1500823.

Fabes, R. A., Leonard, S. A., Kupanoff, K., & Martin, C. L. (2001). Parental Coping with Children’s Negative Emotions: Relations with Children’s Emotional and Social Responding. Child Development, 72(3), 907–920. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1132463

Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54.

Haleemunnissa, S., Didel, S., Swami, M. K., Singh, K., & Vyas, V. (2021). Children and COVID19: Understanding impact on the growth trajectory of an evolving generation. Children and Youth Services Review, 120, 105754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105754.

Hanley, A., Symonds, J. E., & Horan, J. (2022). COVID-19 School closures and children’s social and emotional functioning: the protective influence of parent, sibling, and peer relationships. Education 3-13, 52(8), 1452–1463. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2022.2154615.

Heinrich, C. J. (2014). Parents’ employment and children’s wellbeing. The Future of Children, 24(1), 121–146. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.2014.0000.

Masterson, M. L., & Kersey, K. C. (2013). Connecting children to kindness: Encouraging a culture of empathy. Childhood Education, 89(4), 211-216.

Meins, E. (2013). Sensitive attunement to infants' internal states: operationalizing the construct of mind-mindedness. Attachment & human development, 15(5-6), 524–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2013.830388.

Prime, H., Wade, M., & Browne, D. T. (2020). Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist, 75(5), 631–643. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000660.

Rutherford, H. J., Wallace, N. S., Laurent, H. K., & Mayes, L. C. (2015). Emotion regulation in parenthood. Developmental Review, 36, 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2014.12.008.

Sandford, A (2020). Coronavirus: Half of humanity on lockdown in 90 countries. Euronews. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

Sherman, L. J., Rice, K., & Cassidy, J. (2015). Infant capacities related to building internal working models of attachment figures: A theoretical and empirical review. Developmental Review, 37, 109–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2015.06.001.

Shorer, M., & Leibovich, L. (2020). Young children’s emotional stress reactions during the COVID-19 outbreak and their associations with parental emotion regulation and parental playfulness. Early Child Development and Care, 192(6), 861-871 https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2020.1806830

Staub, E. (2013). The roots of goodness and resistance to evil: Inclusive caring, moral courage, altruism born of suffering, active bystandership, and heroism. Oxford University Press.

Symonds, J., Devine, D., Sloan, S., Crean, M., Martinez Sainz, G., Moore, B., & Farrell, E. (2020). Experiences of remote teaching and learning in Ireland during the COVID-19 pandemic (March–May 2020) (No. Children’s School Lives). National Council for Curriculum and Assessment.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (Vol. 86). Harvard university press.